Introduction

The Greek Lens: Anchored in Virtue and Simplicity

In the marketplaces of Athens and the gardens of Epicurus, the Greeks debated what it meant to live well. The Stoics taught that virtue, like a solid keel, anchors the soul against life’s storms. To them, wealth is not found in gold but in needing little. “Wealth consists not in having great possessions,” Epictetus reminded, “but in having few wants.”

Epicurus, often mistaken as a prophet of indulgence, in truth praised simplicity. He likened desire to a fire: if you continually heap fuel upon it, it rages out of control. But if you tend only to the small flame of natural needs — food, friendship, shelter — it burns gently, giving warmth without destruction. Here again we find the seed of your thought: when the flame of need is tended, the smoke of craving clears, and peace becomes visible.

Taoist Wisdom: Flowing Like Water

In the valleys of ancient China, Taoist sages saw the world as a river — ceaseless, fluid, nourishing all without clinging to anything. Laozi (aka Lao-tzu or Lao-Tze) described the sage as like water: humble, seeking the lowest places, yet indispensable, soft enough to yield, strong enough to carve stone.

The Taoist notion of wu wei — effortless action — teaches that when one ceases to force, the natural current carries them further than striving ever could. To say, “I want nothing,” is to become like the river: flowing, giving, never hoarding. It is not a stagnant pool of resignation, but a living stream that nourishes simply because it is full.

Sikh Wisdom: The Ocean of Contentment

In Sikh thought, the jewel of contentment (santokh) shines at the center of spiritual life. Gurbani declares — contentment is the ocean of all happiness. Just as the ocean does not dry up when rivers pour into it, a contented heart remains vast and undisturbed, no matter how much flows through.

The Sikh Gurus lived this truth not in isolation but in engagement. They tilled the soil, built communities, and fought for justice. Their contentment was not escape but empowerment: when one wants nothing for oneself, one is free to serve the needs of all. In this way, “I want nothing” becomes the highest form of generosity, for the self no longer stands between the individual and humanity.

The Shadow Side: Mistaking Stillness for Stagnation

Yet there is a danger in misunderstanding this wisdom. To want nothing must not be confused with doing nothing. A stagnant pond grows brackish, but a flowing river stays alive. If one interprets “wanting nothing” as refusal to participate in life — as apathy, withdrawal, or denial of responsibility — then the insight curdles into nihilism.

True contentment does not extinguish aspiration; it refines it. The Stoic sage still fulfilled his civic duty, the Taoist still harmonized with the natural order, the Sikh Gurus still engaged in the struggles of their time. The point is not to abandon desire altogether, but to master it, so that action springs not from compulsion but from freedom.

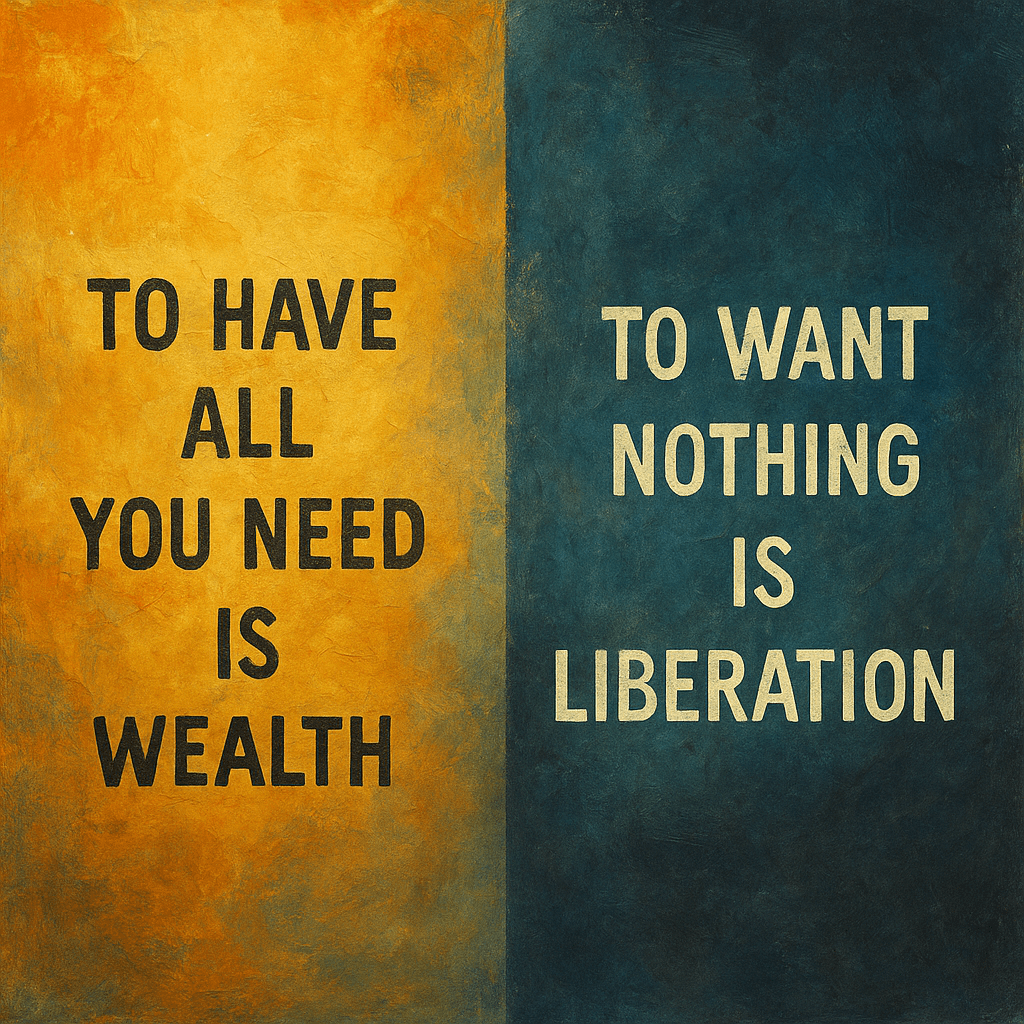

“To have all you need is wealth; to want nothing is liberation.”

Conclusion: The Liberation of Enough

To dwell in the mindspace where “my needs are met, and I want nothing” is to discover a kind of liberation. It is the realization that abundance is measured not by accumulation but by sufficiency. The Greeks called this virtue, the Taoists called it harmony, and Sikh wisdom called it santokh.

Across traditions, the teaching converges: when craving dissolves, one no longer grasps for the world, but lives as part of it — like the river that flows, the flame that warms, the ocean that receives. This is not the emptiness of lack, but the fullness of enough. From this fullness springs the highest freedom: to act not because one must fill oneself, but because one is already overflowing.